REVIEW OF FINDINGS:

LCL SURVEY ON DEPRESSION IN LAWYERS, 2018

With the recent publication of our ABA book, The Full Weight of the Law: How Legal Professionals Can Recognize and Rebound from Depression, co-author Shawn Healy and I were invited to make a presentation on depression in lawyers at the 2018 National Conference for Lawyer Assistance Programs in September 2018.

In an advance teleconference with our 3rd co-presenter, Katherine Myers, JD, she highlighted the issue of stigma as an impediment to depressed lawyers’ inclination to reach out for help. Shawn and I, too, had often spoken to groups of lawyers and law students about aspects of lawyer culture that can have the effect of deterring lawyers from recognizing and addressing their needs as human beings. I thought it would be a nice addition to our presentation if I surveyed lawyers who had received help for mood disorders about the process of recognizing, accepting, and addressing the problem. Getting appropriate help can assist or even save lawyers’ careers, with a resulting positive effect on their clients.

So I wrote up a relatively brief survey, put it online, and had it sent to the attorneys on LCL’s mailing list, most of whom are former clients of ours, with the help of our Marketing Director, Rachel Casper. Later, our executive director, Anna Levine, also sent a link to the survey to the listserv for directors of lawyer assistance programs around the country. It appears to me that many of those who received these emails also forwarded them to other lawyers. My initial guess was that we’d receive perhaps 12 responses, which might yield some interesting ideas. (Don’t ask me how I derived that number, but most people don’t respond to surveys, and this was one that required thought.) The survey was available for response during the month of August. To my surprise, it got a total of 259 responses!

I present below the initial results. (After the conference, I hope to do a more exacting analysis, for example deleting those (about 5%) who indicated that they had not actually experienced depression, and looking for correlations not yet explored.)

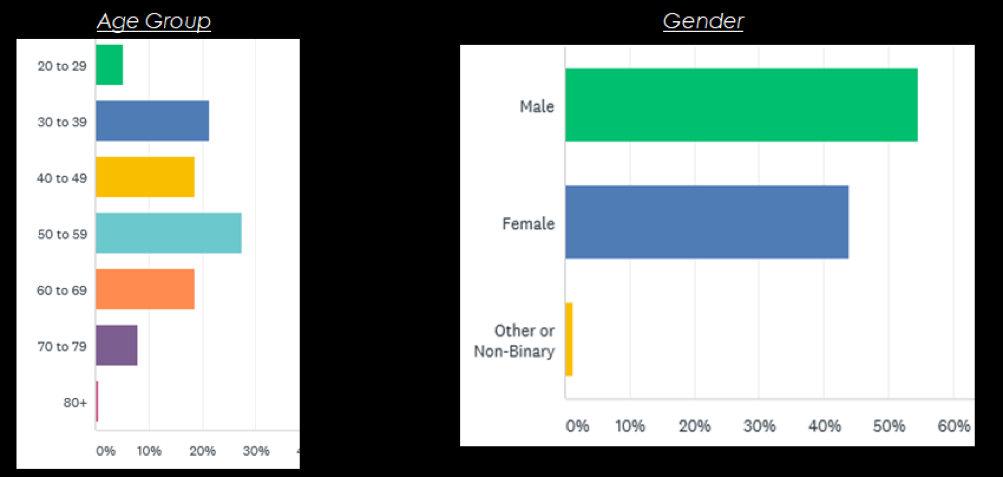

DEMOGRAPHICS

These are self-explanatory in this chart.

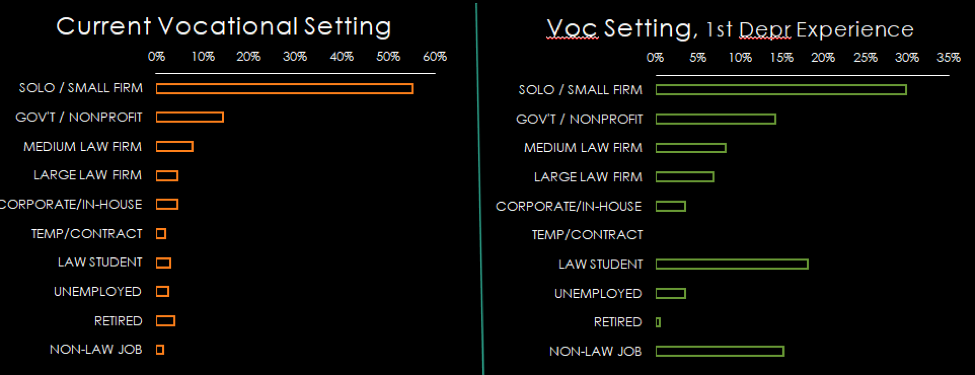

VOCATIONAL SETTING

The majority of our respondents, similarly to the majority of lawyers we see at LCL, are in solo or small firm practice. The main difference between current vocational setting and the work they were doing at the time of their first depression experience is that many more of them were law students, or working outside the field of law (probably before law school), or in government/nonprofit jobs during initial depressive episodes.

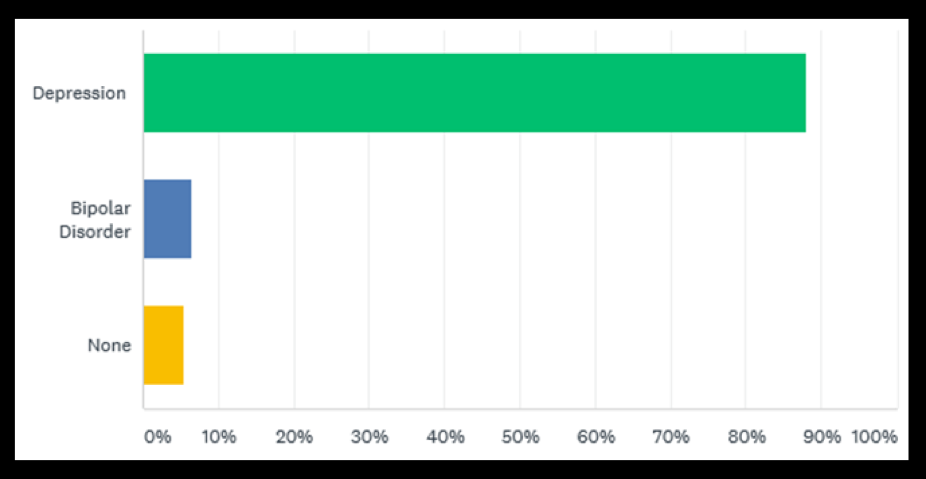

TYPE OF MOOD DISORDER

Among lawyers who responded to this survey, 13 times as many reported (unipolar) depression as reported bipolar disorder (which features manic or hypomanic as well as depressed episodes). In the general population, though figures vary widely across studies, the ratio is more like 5 to 1.

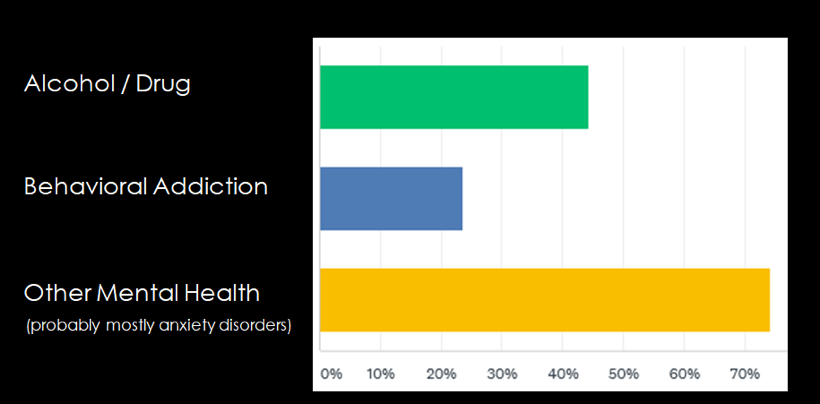

COEXISTING CONDITIONS

Depression often presents itself in a context including other mental health conditions. Aspects of so-called “dual diagnosis” are discussed in our book. Among the attorneys in this survey pool, about 45% had also dealt with alcohol or drug problems, and about 25% had faced so-called behavioral addictions (such as compulsive gambling or sexual behavior). But the most common coexisting condition (about 75%) was “Other.” While I now wish I had broken that down into more categories in designing the survey, I think I’m on solid ground postulating that most of these individuals dealt with one or another kind of anxiety disorder.

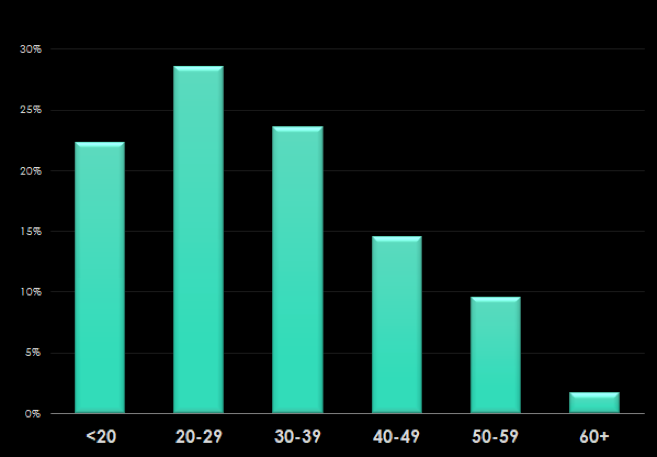

AGE RECOGNIZED DEPRESSION

In the survey, I asked, “At about what age did you come to realize that you suffered from depression (or bipolar disorder)?” In reviewing responses, I surmised that some respondents took the question to mean “Retrospectively, how old were you when you first showed signs of depression,” while others took it to mean, “At what age did you accept that you were dealing with depression.” The answers varied from childhood to senior years, as shown on the graph below.

Since we have reviewed studies that suggest that law school itself, the first immersion in lawyer culture, tends to trigger depression (and alcohol problems), I found it noteworthy that over 20% of the lawyers in the survey had first seen depression in their childhood or teens, and that about half experienced depression before the age of 30.

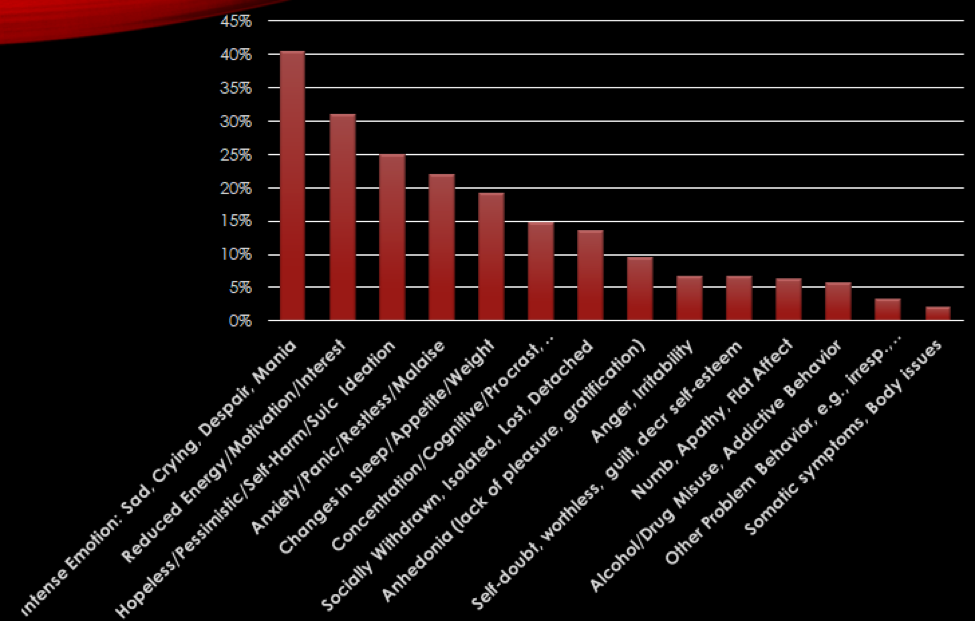

SIGNS OF DEPRESSION THAT FIRST CAUGHT LAWYERS’ ATTENTION

This was one of the items in which the respondents were not forced into a multiple choice, but were given an open text box in which to respond in their own words. I then did my best to categorize the responses. (Apparently there is a software program for automated determination of these factors, and I plan to look into that.) The top 4 categories were: (1) Intense emotion (e.g., crying/despair, or, if manic, feeling very revved up); (2) A loss of energy/motivation/interest; (3) Sense of hopelessness/pessimism, which for some included self-harm or suicidal thinking; (4) Anxiety, panic, or malaise, which can often accompany depression. More subtle indicators, such as getting less enjoyment from formerly pleasurable activities, or declining self-esteem, were not noticed as soon, and for some seem to have been viewed as natural reactions to their work as lawyers. Some of the survey-takers were quite expressive in their descriptions of the depressive experience, e.g., “Walking through mud;” “Inability to take action;” “Every little issue seemed like a mountain.”

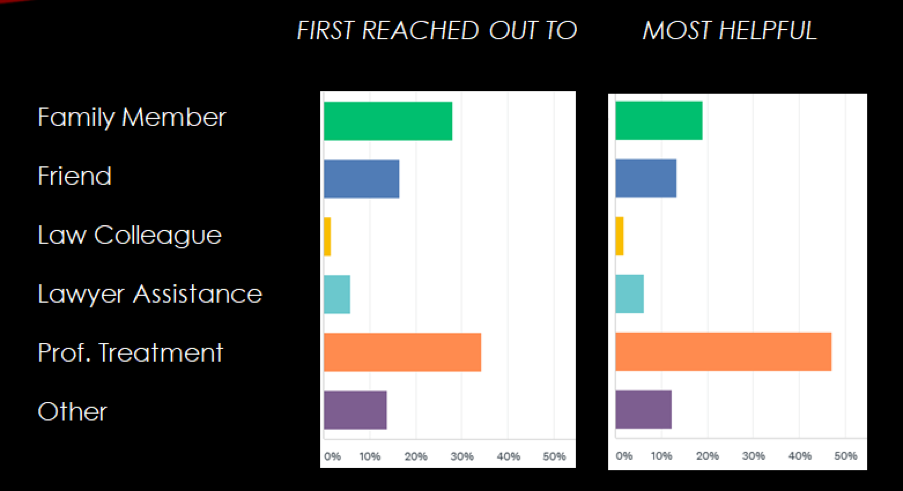

GETTING HELP AND SUPPORT

Perhaps not surprisingly, lawyers were least likely to turn to their professional colleagues for support around depression. Professional treatment was most often the first source of assistance (just ahead of family), and far exceeded others in helpfulness. This does not mean that we’d recommend limiting one’s help-seeking efforts only to professionals – friends, family, and understanding peers are immensely important sources of support.

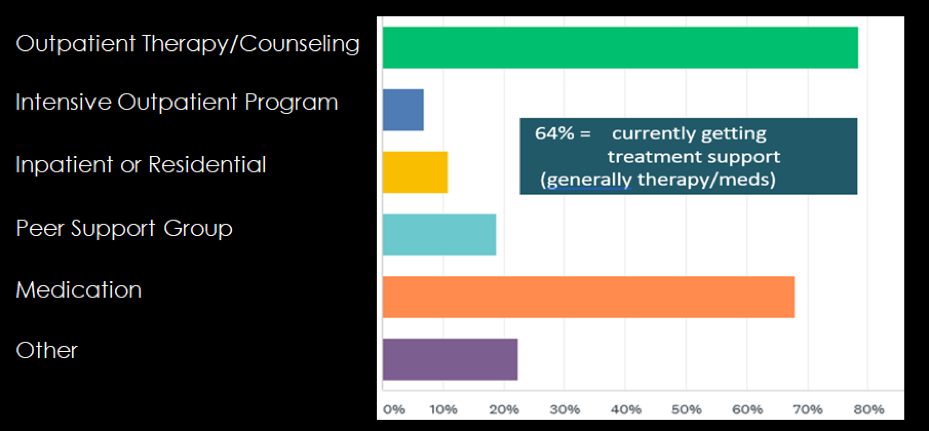

Among the types of treatment received by depressed lawyers participating in this survey the two top categories by far were outpatient therapy/counseling and medication. But more than 10% had also received inpatient or residential treatment, and about 6% had participated in an intensive outpatient program (in which the patient is not hospitalized but participates in treatment several days per week). 64% of respondents were currently in treatment (generally outpatient therapy and/or medications), which makes sense since mood disorders are often chronic or recurrent.

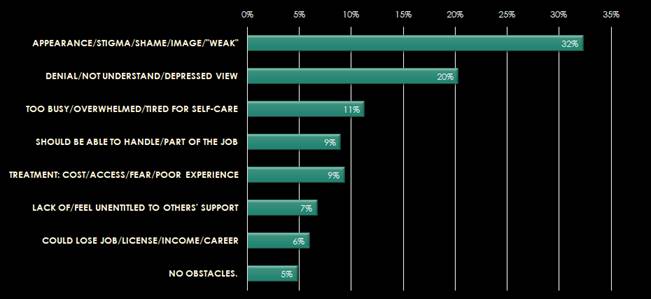

OBSTACLES TO RECOGNIZING DEPRESSION AND GETTING HELP

This was another item in which respondents answered in their own words, and I grouped their replies into categories. By far the biggest factor standing in the way of getting effective help for depression was a concern with appearance and/or stigma. Some lawyers reported feeling ashamed of having a mood problem, of a perception that depression would be viewed, in the world of attorneys and clients, as a sign of weakness. In addition, 20% of lawyer respondents indicated that they were either in denial about being depressed or did not understand that they were experiencing symptoms of depression; some reported what I called a “depressed view,” e.g., a sense that to work in the legal field entails feeling, for example, demoralized or unmotivated.

All of these obstacles are worthy of our attention. One that particularly concerns me, reported by 9% of respondents, is barriers to actually connecting with treatment. Some reported that their first contacts with treatment providers were discouraging. Many reported difficulty gaining access to or affording treatment – I’m all too aware, in my work at LCL (which largely involves making referrals of lawyers after clinical evaluation), that it is often very challenging to find providers who are not only covered by one’s managed care plan but have openings for new patients. Some coverage plans seem as if they were designed to prevent people from using their benefits. Many providers, too, only see people on a self-pay basis, largely because contracting with HMO plans typically involves accepting close to a 50% fee discount. Getting a referral through a lawyer assistance program is still much more likely to result in good treatment than randomly choosing a name on an insurance list, but each year the process seems to become more difficult. Don’t get me started. Of course, this is less of an issue for lawyers who can afford to self-pay.

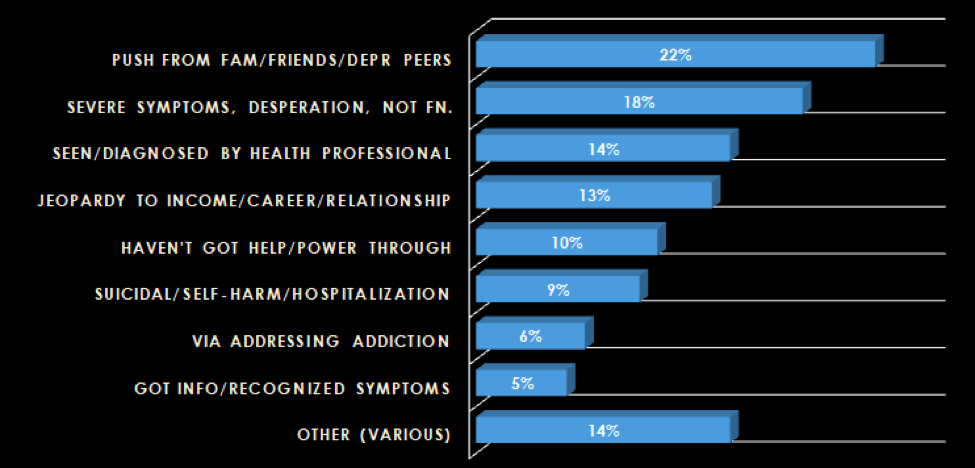

OVERCOMING OBSTACLES

Although family members and peers were not described (see above) as the biggest source of help for depression, they did have a great impact on encouraging or pushing depressed lawyers to reach out for help despite all of the obstacles described above. As is the case when it comes to addictions, peers who have, themselves, experienced the problem can be particularly potent motivators. Severe symptoms that interfere with normal functioning can also offer the requisite push (this 18% becomes 27% of respondents if we include becoming suicidal or requiring hospitalization), as can hearing a diagnosis of depression from a health professional such as one’s primary care physician. Some lawyers reported reaching the inescapable conclusion that their income, careers, or primary relationships would be jeopardized if their depression progressed. A surprising number of survey takers (10%) reported that, though depressed, they had not sought help, some feeling that it was their duty to find a way to “power through” – essentially buying the view that depression is equivalent to weakness.

CLOSING WORDS

In the final item of the survey (other than offering the opportunity to give name or email address in what was otherwise an anonymous survey), I asked for, “in your own words, any additional comments that would better convey your experience in a way that could be helpful to other lawyers.” While noting that some of the comments offered were from a negative perspective, I offer here a smattering of selected constructive comments:

“I am not a machine that can do intensively detailed emotionally exhausting work for 9-10 hours a day on little sleep, poor diet, and with no time for exercise or for friends and family. Stigma I can deal with – work conditions that make my existing challenges harder, I can’t.”

“Lapses in getting work done or turned in is a huge indicator that there is more going on. Our system is one of confrontation rather than truth finding which tends to make weakness a tool for winning rather than a cause for alarm for the health of a colleague.”

“No one in my family even knew I was suffering…. It was really hard …telling everyone …because it felt like I was admitting that I was a failure and that I was weak… The social stigma is hard to overcome, but if you had diabetes you wouldn’t hesitate to get medical help. Depression should be no different.”

“There is a lot of human decency to be found even among opposing litigators, but you have to ask for it. Nobody wants to see a colleague decompensate and most of us will bend over backwards to help.”

“There is no down side to treating this illness: you will feel better and you will be a better family member, friend and lawyer.”

“Please, if you are suffering from depression or anxiety (or both) get help. Tell your spouse. Tell your partner. Tell a colleague. Ask for help. Asking for help does not make you weak. It takes profound strength to ask for help. You can get better. You can get your life back.” — From “Faculty Lounge” blog via survey responder Brian Clarke of Vermont Law School, who is public about his experience with depression.

Jeffrey Fortgang, PhD

Clinical Psychologist

Staff Clinician, LCL Massachusetts