A new 2020 metastudy weighs in on a technique to create confidence featured in Amy Cuddy’s 2012 TED Talk (now with 58 million views), which critics labeled as pseudoscience.

THE THEORY

Presenting yourself as a confident is a key attribute for success in any profession, particularly those as challenging as the practice of law. The art of presentation is an integral aspect of the legal profession, regardless of your particular practice. Good presentation skills matter, whether you are providing direction and counsel to a client, wooing potential referral sources or influencing a judge or jury at trial. Essential to your presentation skills is the ability to project confidence and power to those you wish to influence. This goes for new and experienced practitioners alike. And it all begins with the way in which you view yourself. If you don’t believe in your abilities, then how can you persuade others to trust and respect you?

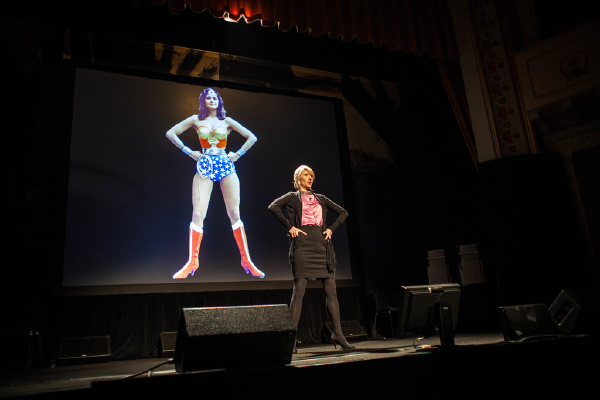

For those who struggle to feel confident, Amy Cuddy (then a social psychologist at Harvard) revealed a solution in her 2012 TED Talk, Your Body Language Shapes Who You Are. Her talk — now with 58 million views — shares her research on how power posing can change not only how others perceive you, but also how you perceive yourself. She found that by embracing a high-power pose for two minutes, you can increase levels of testosterone by 20 percent and decrease levels of the stress-related hormone cortisol by 25 percent. With these physical changes transforming the how you think and feel about yourself, you can thereby project a more positive and confident image to others.

Concluding her talk, Cuddy described a challenging personal experience where she was convinced she would fail. Her college advisor told her to fake it until you make it. Amy says she used that approach through undergrad, graduate school and as a teacher until she forgot that she was faking it and actually became it. Her message is that power posing will feel like you’re faking confidence. But because your body position is a tool that creates confidence, “faking it” will help you become it.

QUESTIONS OF VALIDITY

But the validity of her results has been questioned. When some researchers failed to replicate her results, most of the research community responded beyond questioning the validity of her results with uniquely harsh criticism. Her coauthor even abandoned any defense of their work. In 2017, The New York Times published a pretty fascinating story on why The Revolution Came for Amy Cuddy, revealing culture changes in academia that shaped the disproportionate backlash. In April 2018, Forbes published more enthusiastic support of Cuddy’s work. In 2016, New York Magazine published Amy Cuddy’s overview on the state of the science on postural feedback (power posing) and some comments on civilized scientific discourse.

A June 2020 meta-analysis of 73 studies shows “it is non-controversial to say that the way we approach the world with our physical bodies shapes the way we think and feel.” (Study author Mia Skytte O’Toole, professor at Aarhus University in Denmark in this Forbes article.) Social psychologist and Northwestern University professor Eli Finkel provides further context in the same article:

“Many people were skeptical that power posing had the sorts of positive effects that Cuddy said they did. And, indeed, replication efforts haven’t shown the same level of support for the hormonal effects that the initial study showed. But what is weird is that the results—preregistered, rigorous replications from scholars who were deeply skeptical of the effect—kept showing that the core effect is robust. Postural expansiveness versus contractiveness does indeed make people feel more powerful. The effect isn’t huge, of course, but it’s clearly there.”

IN CONCLUSION

Power posing is worth trying. Next time you are gearing up to make a presentation, meet with a client or give an opening statement, take two minutes to “power pose” and see how it impacts you and your audience. As you learn about any new research, stay mindful of how you can use it. If there’s dubious causality but no risk and little time commitment, you might stand to gain even if it’s just from the placebo effect. And

Self-affirmation can help too. As Amy Cuddy explains for Big Think, taking time to remind ourselves what our values are and why we hold them can help us feel more powerful. You can find guidance on aligning your values with your work as a lawyer in the second workbook in our Career Research & Development Series.

One final tip to really improve your confidence: Don’t judge others. As LCL MA Clinical Psychologist Dr. Shawn Healy explains,

Most people at some point in their lives experience what is known as the Imposter Syndrome. This is when a person feels like he/she is a fake or significantly inadequate as compared to those around him/her. We often judge others by what they show us (usually the best image they can muster), while we judge ourselves based on all the positive and negative information we have on ourselves. This can result in an overly positive view of others’ competence and an overly negative view of our own abilities. Practicing a “power pose” should involve very little risk, and can help quickly boost your confidence.

To sustain your confidence boost, I recommend this surprisingly effective technique: Try to avoid judging others. Replace judgment with the view that everyone else is “a person with doubts and flaws, and tries the best they can, just like me”. It might not feel easy for awhile, but each time you resist judging someone else, your brain moves further from concerns about when and how others are judging you.

Free & Confidential Consultations:

Whether for persistent struggles with confidence or any other concern — lawyers, law students, and judges in Massachusetts can discuss concerns with a licensed therapist, law practice advisor, or both. Find more on scheduling here.

. . .

A previous post titled Can Power Posing Help Lawyers Gain Confidence? (which was an update to Maximize Your Impact by Boosting Your Internal Image, which originally appeared in the Massachusetts Bar Association’s eJournal) no redirects here.