This 3-part planning guide is designed for bar association leadership in Massachusetts to create and effectively charge a Well-Being Committee.

This guide was created by Susan Letterman White, JD, MS, Mass LOMAP, with gratitude to Marianne LeBlanc, Co-Chair, Massachusetts Bar Association Well-Being Committee, and Grace Garcia, Co-Chair, Massachusetts Bar Association Well-Being Committee.

New Resource!

Our LCL MA clinical staff contributed to a Lawyer Well-Being Toolkit for Bar Associations in Massachusetts, published by the MBA and SJC Lawyer Well-Being Committee in February 2021.

. . .

INTRODUCTION

Well-being in the legal profession requires community-wide effort. The Massachusetts Bar Association has successfully launched a Well-Being Committee, and we encourage others to as well.

This guide provides instruction and templates for the process of creating a Well-Being Committee, which is broken down into three phases. To charge a group in your bar association’s leadership with improving the well-being of the membership, focus on action steps in three consecutive categories — although these phases are being explained as distinct, in practice there is overlap:

- Select and Develop Your Team. First, select and develop a committee. Your committee is your team, unless it is large enough to break into subcommittees to do the actual work.

- Identify Team Goals. Next, identify content and outcome goals and create sub-committees, if your committee is large enough. Your teams will be charged with delivering content and experiences to bar members.

- Design, Deliver, and Adapt. Finally, give your teams the time to design or curate content and offer content, programs, and experiences to your bar members. Over time, based on feedback from your members, you’ll adjust offerings.

1.

PHASE 1: SELECT AND DEVELOP YOUR TEAM

This phase involves planning for Team Size; Roles and Responsibilities; and Process.

Teams are groups; however, not all groups are teams. Teams are groups of people with complementary skills and interests committed to a common approach and the team’s purpose. When working well, team members hold each other mutually accountable and deliver quality projects. Teams have clear goals, roles and responsibilities, regular meetings, helpful processes, and sufficient resources.

Team Size

Too few or too many people affect the ability to work together productively. Larger teams generate more ideas and also more chaos. Effective teams are generally 4-6 people. Research suggests that team interaction and productivity drop with teams of more than 10 people. That said, in any bar association, take on all members with an interest in contributing to your well-being initiative and break the committee into smaller sub-committees, each with a different goal. There enough opportunities to design and deliver content related to well-being to identify a large variety of goals for different subcommittees to pursue.

Most importantly, invite people with an interest in and ideas about well-being onto the committee. Once you have your team, share contact information.

Roles and Responsibilities

All committees and subcommittees need a leader. This is especially true for virtual teams. Leaders are responsible for organizing meetings, keeping the work of the team aligned with the goals of the organization, measuring and reporting to the organization on the team’s progress towards its goals, project management of all subcommittees’ work, and getting the right resources where and when they are needed. To do all this, the best leaders regularly solicit feedback and ideas from team members, ask questions, and provide due dates and processes to keep projects on track. There is nothing worse than to have someone in a leadership role that would prefer not to be. Leaders must ensure that team members have clear direction what people are supposed to do and due dates.

Click here for a project management template to track roles and responsibilities.

Team Processes

One of the best processes for keeping people moving toward their goals, is the use of regular meetings with a detailed agenda that identifies the specific topics in need of group discussion and decision-making. Use emails to simply pass along information that does not require discussion information that should be digested before a group discussion at a meeting.

Click here for a meeting agenda template.

2.

PHASE 2: IDENTIFY TEAM GOALS

The goals of your committee are to select and deliver the well-being content and experiences to bar membership. Content areas are discussed in this section. Content creation may be a result of curating existing content and/or developing original content. Content may be delivered in a variety of ways from written articles to presentations, workshops, mentoring, and support groups, all of which LCL MA can assist with. This section covers: What Is Stress (Distress)?; Causes and Consequences; and Managing Stress (Distress).

As you read this section, use this project ideas template to capture content and delivery ideas as they arise.

Click here for a project management template.

Purpose of Your Well-Being Committee

One obstacle to lawyer well-being that bar associations can help ameliorate is the stigma associated with needing mental health support, guidance, resources, and treatment. By normalizing these needs, and also addressing other cultural norms that perpetuate stigma, bar associations will be key contributors to a healthier profession.

The Massachusetts legal community needs and wants tips, techniques, support, and information on the importance of Well-Being. Today, more than ever, we can’t overstate the importance of avoiding stressful situations that lead to a decline in mental health and ineffective means, such as substance and alcohol abuse, of address stress. The value to health and happiness that comes with learning how to minimize stressors or respond effectively to the rising tide of stress from work and nonwork is huge.

To that end, all goals will fall under one or more of the following categories for purpose of organizing the work of your committee members.

- Curate resource from existing content – programs, articles, tips, blogs, etc.

- Create or produce original content – programs, articles, blogs, etc.

- Deliver original programs and presentations

- Invite experts in to deliver presentations and programs

- Create support groups or mentoring relationships

Further, all goals will relate to either education and pushing out information, developing skills, or providing support. Content will fall under explaining what stress is, its causes and consequences, and managing it. An important element of well-being is diversity, equity, and inclusion.

What is Stress?

Stress is a way of adapting to a situation perceived as challenging or threatening one’s well-being. (J.C. Quick et al., Preventive Stress Management in Organizations (Washington DC: American Psychological Association, 1997) pp. 3-4; R.S. DeFrank and J.M. Ivancevich, “Stress on the Job: An Executive Update,” Academy of Management Executive 12 (August 1998), pp 55-66.)

Stress can be helpful or harmful “distress.” One of the early stress researchers, Hans Selye, developed a stress experience model that illustrates the experience as an automatic response to cope with environmental demands.

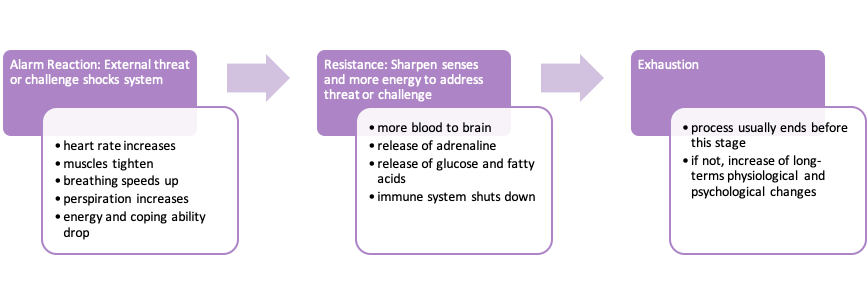

Stress involves three stages according to this model:

- Alarm Reaction: A shock to the system. A threat or challenge from the external environment activates physiological responses: Our heart rates increase, muscles tighten, breathing speeds up, and perspiration increases. Our energy level and coping effectiveness decreases in response to initial shock.

- Resistance: Our ability to cope with the situation rises above normal. Our bodies move more blood to the brain, release adrenaline and other hormones, fuel the system by releasing more glucose and fatty acids, activate systems that sharpen our senses, and conserve resources by shutting down our immune system. This gives us more energy to address the cause of the stress.

- Exhaustion: If the source of stress persists, we eventually become exhausted. Usually the process ends before this stage; however, when it does not, it can increase the risk of long-terms physiological and psychological changes.

Hans Selye’s Stress Experience Model

Stress may be work-related or nonwork-related. Also, not all stress is distress – stress that leads to unhealthy consequences that we would like to minimize or eliminate. We need some level of stress as momentum or motivation to respond to challenges. And a healthy perspective on the nature of threats is a key differentiator.

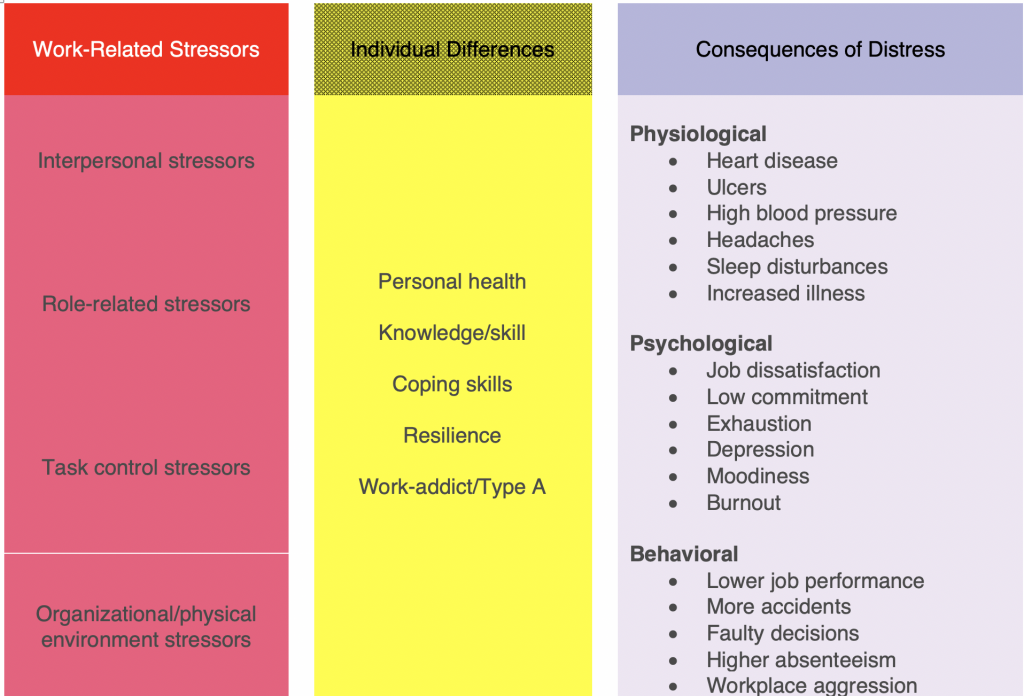

What are the causes and consequences of stress?

Stressors, causes of stress, may lead to consequences of distress and whether they do depends on individual differences. At any given point, some people have a high, inner resilience to certain types of stress for a variety of reasons, while others have a lower resilience. A high inner resilience can be developed.

Causes of Stress

Stressors can be anything that creates a physical or emotional demand on a lawyer. It is not uncommon, in today’s COVID -19 world, for people to feel increased physical or emotional demands from too much work, job insecurity, worries about health, information overload, social isolation, too many meetings, technology demands, and the increasing pace of life.

Even without the additional pressure from the pandemic, the trend toward more interaction with co-workers, especially for lawyers who went into the field to work independently, can feel overwhelming. These interpersonal stressors also include organizational politics, bad bosses, and incivility.

Dealing with professional incivility is frustrating and exhausting for many lawyers. It may show up in an email, a phone call, or face-to-face interaction. Lawyers can choose to be uncivil or incivility can show up as a consequence of feeling overly stressed. The intentional use of incivility as a bullying tactic and the inadvertent incivility that results when a lawyer is unaware of personal emotions and unable to manage them often causes stress to those lawyers on receiving end.

Role-related stressors arise when a person doesn’t understand the responsibilities of another role or is having difficulty reconciling or performing various roles with conflicting responsibilities. A lack of understanding may arise if there is a lack of clarity about the tasks and social expectations of the role or if the role is not a good fit for the person’s skills. Role conflict arises because a requirement of one role impinge on the responsibilities of another or where personal values are incompatible with organizational values. It also arises when people are expected to act differently at work than in nonwork roles. For example, lawyers are expected to act logically and impersonally in many aspects of work and it may be difficult to switch to more compassionate behavioral style in the lawyer’s personal life or when supporting a client’s emotional needs. Lawyers benefit from developing an awareness of their emotions and learning how to manage them. That means training in emotional intelligence (EQ). When lawyers learn to pay attention to their career choices, communication skills, and relationships, they are better able to avoid overly stressful situations or better manage themselves in those situations.

Related to role-related stressors is the blurring of boundaries between work and nonwork or rest. This leads to work overload and may lead to job burnout, if not caught and addressed early enough. Meeting work and personal life demands is increasingly difficult for lawyers. The COVID-19 pandemic, has for some people, led to working longer work hours and little energy left for one’s family, friends, or oneself, and barely a boundary between one’s work and personal life. The strain from one domain can easily spill into another. Even without this pandemic, blurring of boundaries happen when stresses from relationships, finances, loss of loved one, moving, birth of child, buying a house and a new mortgage, care for parents and elderly family members impinges on work or vice versa. Learning how to manage time and boundaries are skills that all lawyers can learn and develop.

Task control stressors arise when something that is required to perform the task successfully is blocked. For example, a lawyer may feel responsible for the outcome of litigation even though the facts favor the other side or the court’s docket is slow. These situations present obstacles beyond the lawyer’s control. Another example is that most lawyers like to control their work schedule and processes, but technology, which is helpful for efficiency can be difficult to use and make it more difficult to protect personal time and privacy.

Environmental stressors whether working in a firm or as a solo practitioner include reduced job security when the economy shifts and the need to rapidly and constantly adapt to other unexpected, environmental changes and shifts in client preferences and expectations. When a lawyer survives a layoff, it is often accompanied by survivor’s guilt and an increased workload. When clients demand more efficiency and reduced costs, lawyers must change their business models and find ways to deliver more in less time. Whether working from home or in an office, excessive noise, poor lighting, and the use of space can increase stress. Lawyers can improve their self-awareness of attitudes, ability to adapt to change, and even workplace surroundings with the right information and a few new skills.

Individual Differences Affecting Stress Experience and Response

People have different perceptions of what is stressful. What may be stressful to one person may be energizing to another. An easy example to understand this concept is not everyone likes rock climbing. Some people feel anxious, just thinking about doing it, while others find doing it simultaneously exhilarating and relaxing. People can change their mindsets toward various stressors.

Different people also experience different threshold levels of resistance to stress and resilience in its face. Some theorists say that this is a fixed matter of personality, yet personality isn’t entirely fixed itself. Higher stress resilience correlates with personality traits of high extroversion, low neuroticism, internal locus of control, high tolerance of change, and high self-esteem. While it does require work, an internal locus of control and high self-esteem can be learned through unlearning thinking patterns, or “cognitive restructuring”.

Many theorists say that resilience, the ability to cope successfully with significant change, adversity, or risk, is a skill that can be developed with practice. People with optimism, confidence, and positive emotions tend to be more resilient. This is at the core of cognitive behavior techniques, adaptive leadership skills, and positive psychology. Susan worked with a client, who described both anxiety and excitement with the same language of an increased, rapid heart rate and breathing. When that was brought to the client’s attention, it opened options for perspective shifting and substituting the unconscious behavior connected with anxiety to that connected with excitement. Changing one’s emotions and behavior becomes possible with perspective shifting. In this situation the perception of risk and decision of whether to take on a new client and legal matter changed. The change affected stress levels related to the law firm’s financial situation and the lawyer’s options for creating the intellectual stimulation that makes the practice of law exciting and fun.

We can cultivate resilience in many ways. Each of these options could be the core of a program or article for your committee.

- We can cultivate good health. Although younger people tend to experience fewer and less severe symptoms of stress, this is not always true. Regardless of age, we can improve health with exercise and a healthy lifestyle.

- We learn and improve a skill through practice. The level of experience with a task affects stress. The newness of a skill comes with a level of stress that mastery does not. Practice, not only makes “perfect,” it reduces performance anxiety.

- We can develop a variety of coping skills, such as:

- Managing boundaries;

- Seeking social support by finding or creating groups for social support or mentors and mentees;

- Perspective shifting, checking for assumptions and conclusions, and making better, fact-based decisions using techniques from psychologists. Aaron Beck, founder of cognitive behavior therapy and Albert Ellis, founder of rational emotive behavior therapy developed techniques to help people shift their thinking and change how they were feeling and what they were doing. Leadership researchers took these techniques and adapted them to teach people how to better manage their feelings and behavior through deeper awareness of their thought patterns and self-talk that limits options for problem-solving and decision-making.

- Developing and improving emotional intelligence, visual intelligence, and consequently problem-solving skills to analyze the source of stress and find ways to neutralize a problem instead of denying or ignoring it or noticing exiting challenges and taking them on. People with a higher emotional intelligence and better problem-solving skills are better at stress management.

- Developing a sense of purpose and awareness of personal values. People with a clear sense of purpose and values manage stress better, select career paths aligned with their interests and values, and avoid choosing jobs where personal and organizational values conflict.

- We can learn to distinguish between being an enthusiastic work addict; i.e., having high work involvement, drive to succeed, and work enjoyment and being a workaholic on the way to job burnout.

Consequences of Distress

When stress passes the point of helpful motivation, there is no benefit to denying distress. Doing so only leads to unhealthy and undesirable physiological, psychological, and behavioral consequences.

Physiologically, stress shuts down our immune system and has been cited as a cause of tension headaches, muscle pain, back problems, cardiovascular disease, and hypertension.

Psychologically, excessive stress has been correlated with job dissatisfaction, moodiness, depression, lower job commitment, and emotional fatigue. Job dissatisfaction can lead to job burnout, with emotional exhaustion, cynicism, and reduced feelings of personal accomplishment from prolonged stress.

Excessive stress also has been correlated with moodiness, depression, and emotional fatigue (aka compassion fatigue), which can lead to emotional exhaustion. There are three stages to emotional exhaustion:

- Stage 1 – Tiredness: This stage is marked by a lack of energy and feeling that one’s emotional resources are depleted.

- Stage 2 – Cynicism, also known as depersonalization. This stage shows up as:

- An indifference toward work and the treatment of others as objects;

- Being emotionally detached from clients and cynical about the organization and job; and

- Strictly following rules and regulations instead of understanding the needs of others and searching for a mutually acceptable solution.

- Stage 3 – Reduced professional efficacy also known as reduced professional accomplishment: This final stage is marked by feelings of diminished confidence about performance and a sense of learned helplessness because one’s efforts appear to not make a difference.

Lawyers should monitor themselves for emotional fatigue. Law is a helping profession and job dissatisfaction is more common in helping occupations.

Behaviorally, excessive stress shows up as reduced job performance, impaired memory, more frequent, accidents, and less effective decisions. Additionally, it is not uncommon to see higher absenteeism due to illness or from exhaustion and verbal harassment towards others. Acting out in the workplace may be the side-effect of less patience and empathy for co-workers, a belief of being treated unfairly, or frustration with a lack of control.

How Can We Manage Stress?

A conceptual division of different content areas and formats for delivery makes it easier for your committee to select content and deliver design options. It also helps with marketing your well-being content to bar members.

Eight dimensions of wellness have been identified through SAMHSA’s Wellness Initiative. SAMHSA, The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration within the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, leads efforts to advance the behavioral health of the nation and to improve the lives of individuals living with mental and substance use disorders, and their families.

SAMHSA’s 8 Dimensions of Wellness

- Emotional: Coping effectively with life and creating satisfying relationships

- Environment: Good health by occupying pleasant, stimulating environments that support well-being

- Financial: Satisfaction with current and future financial situations

- Intellectual: Recognizing creative abilities and finding ways to expand knowledge and skills

- Occupational: Personal satisfaction and enrichment from one’s work

- Physical: Recognizing the need for physical activity, healthy foods, and sleep

- Social: Developing a sense of connection, belonging, and a well-developed support system

- Spiritual: Expanding a sense of purpose and meaning in life

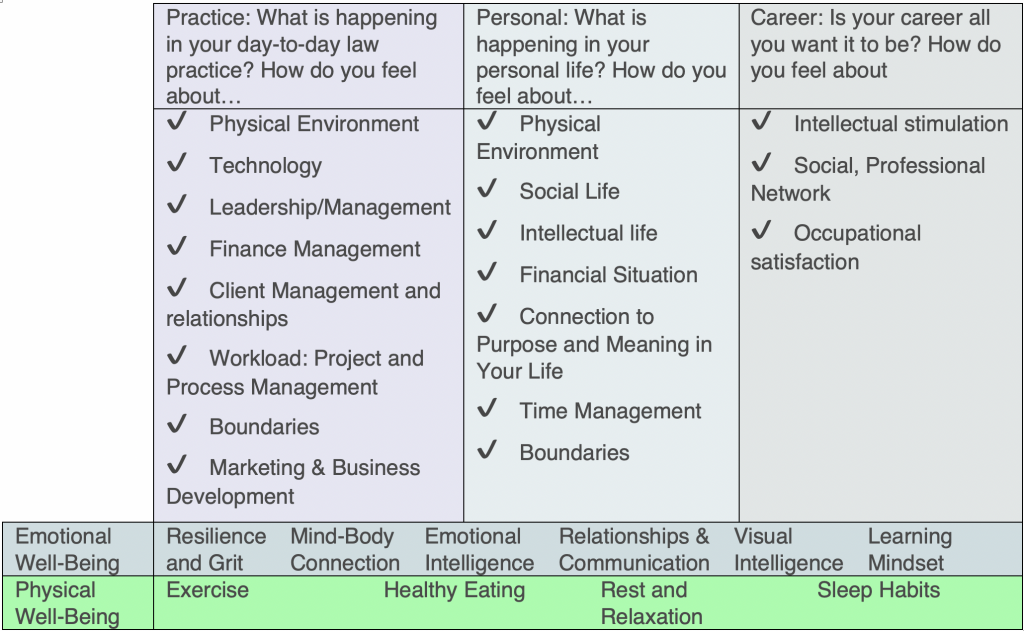

To tailor content to the life of a lawyer, you may want to use language more closely aligned with the day-to-day experiences of lawyers. What are they doing to bring well-being into their: practice, personal life, and career? What are they doing to maintain physical and emotional well-being, which cuts across all other dimensions?

Dimensions of Lawyer Well-Being

If you are an organizational leader interested in removing or reducing stress in the workplace, you may first want to determine the presence of stressor through an annual stress index survey and then develop a plan. The plan may require a culture change to the workplace or changes to the physical space. Alternatively, it may be a decision to change some aspect of the business model, offer skill training, or add a new HR benefit. Consider content on teaching law firm leaders how to develop a survey or provide them with a sample survey.

Culture changes may include encouraging people to find a better balance of work and personal life priorities through flexible work arrangements, less focus on in-the-office, face-time, a switch from time-based performance metrics to outcomes-based metrics, and rewarding healthy lifestyles. Encourage deeper awareness and mindfulness by incorporating a workplace norm of regularly asking of questions such as: Are you a workaholic or work enthusiast? Are you emotionally fatigued or on your way to emotional exhaustion? If possible, offer Employee Assistance Plans and counseling to cope with stress. Create mentoring relationships to help newer lawyers and more seasoned lawyer help each other in areas of weakness. Add in humor and reminders to take breaks – even if only to stand up and walk around every hour or so.

Workspace changes make the physical environment more conducive to less stress and include spaces in the workplace that are conducive to a quick, temporary withdraw from stressors. Consider the noise level, ability for both engagement and disengagement from others, color schemes. In What science, color psychology, and interior designers tell us about creating a comforting space, Diana Budds writes about the affect one’s physical environment has on stress reduction.

Too much emptiness causes stress levels to rise. Spaces that are disorganized or chaotic also cause stress. Organized complexity, like the fractal patterns often found in nature, are soothing. The right temperature of light at the right time of day is essential for regulating our circadian rhythms and helping us sleep better. Texture is very important to calming the mind since the act of looking at something stimulates the same sensations as interacting with it.

If a glitch in the business model or leadership is causing stress, reduce it by setting clear role and responsibility expectations, offering flexible work time and sufficient paid time off for child-care or elder-care, and sufficient training in interpersonal skills training to learn how to recognize and dissipate stress-related behavior in oneself and others.

We can help ourselves and organizations can offer programs on how to better eliminate, reduce, or manage the consequences of stress. Send out the message to avoid avoidance. Do not deny feelings of stress. Avoidance becomes another stressor on top of the one creating the stress in the first place.

Offer support groups, mentoring opportunities, and career development presentations, workshops, and coaching to show people how to find a job that is a good fit with their values and skills and to expect stress from one that is a bad fit. LCL MA is a free resource for Massachusetts organizations to collaborate with on programming related to lawyer well-being — find more here. Offer workshops on the skills of adaptive leadership, CBT, and REBT – how to reframe a threat as a challenge, anxiety as excitement, etc. Other topics may address topics specific to certain practice areas, such as vicarious trauma. Other topics include:

- What stress is, its causes and consequences and quick tips to eliminate, reduce, or manage;

- Time, project, task management – Learn to break down complex work assignments to smaller sets of tasks and assign them to a date and time;

- Improving interpersonal communication skills;

- Improving the ability to set boundaries;

- Developing self-confidence, resilience, grit, learning mindset, adaptive leadership, mindfulness

- Developing clarity of personal goals, strengths and weaknesses, motivation, etc;

- Exercise, relaxation, yoga, and meditation programs to learn how to control the consequences of stress; and

- Healthy eating programs.

Schedule a committee brainstorming meeting to elicit content ideas. When brainstorming, remember to withhold evaluation and judgment of ideas until the very end of the session. Use the Project Ideas template to capture ideas while reading this guide and brainstorming in your committee.

3.

PHASE 3: DESIGN, DELIVER, and ADAPT

This phase involves designing, delivering, and adapting content and experiences to meet your members’ needs and preferences. Designing content includes creating and curating existing content. (LCL MA can help, and is a free resource for Massachusetts bar associations.)

Once your committee has content ideas, prioritize them and assign topics to sub-committees. For each topic, discuss and decide the type of delivery and whether to create content internally in your team, solicit an outside expert for help, or curate existing content for delivery. For example, if your team was working on a plan to delivery content to members on the topic of time management, your team will need to discuss and decide whether the content should be in the form of an article, workshop, or presentation. Should it be delivered in person or virtually? Will your team create and deliver the content or solicit the help of an outside expert?

Use this project management template for individual content topics. The same content can be repurposed for different delivery formats. Articles can become presentations. Education through a presentation can become a “hands-on,” facilitated workshop. Content with wide appeal that evokes personal stories cans set the stage for support groups or one-to-one mentoring or coaching.

Regardless of the content and delivery method, make sure to ask for feedback at the end by including an evaluation form. Click here for a feedback form template.

Free & Confidential Collaborations

LCL MA offers Free & Confidential services for the Massachusetts legal community. Find more here on collaborations on well-being programming and further support.